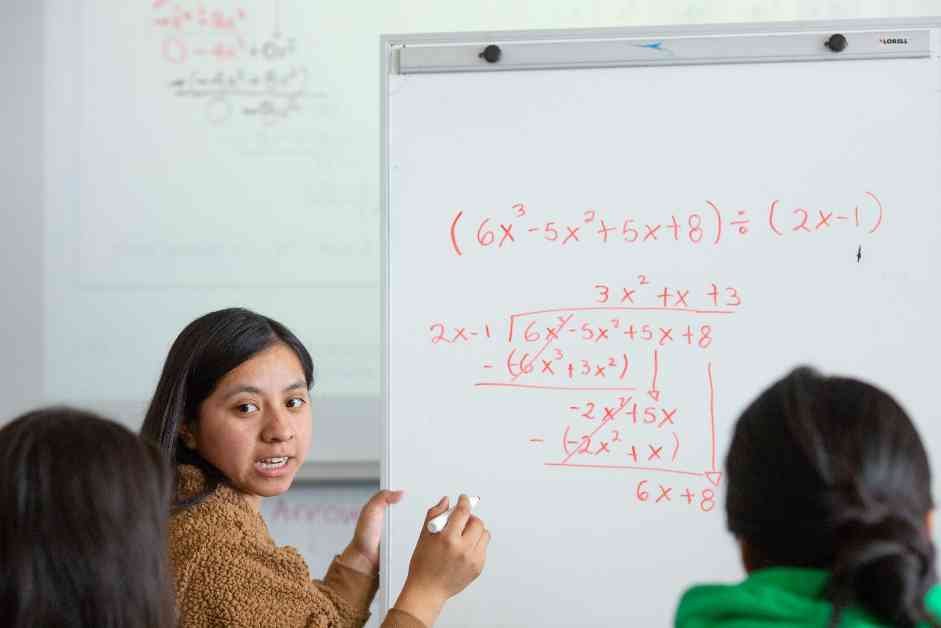

The importance of providing extra academic attention to students has been a topic of discussion for many years, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Matthew Kraft, an associate professor of education and economics at Brown University, has been a strong advocate for expanding tutoring services to more students, regardless of their socio-economic background. However, a recent study conducted by Kraft and his team has revealed some surprising results that have sparked a reevaluation of the effectiveness of mass tutoring programs.

The Study’s Findings

After the pandemic forced schools to shut down in the spring of 2020, Kraft and a group of academics pushed for increased investment in tutoring programs to help students recover from learning losses. Many schools across the nation heeded this call and implemented intensive tutoring initiatives. However, the results of Kraft’s study, which tracked almost 7,000 students in Nashville, Tennessee, between 2021 and 2023, painted a less optimistic picture.

The study found that while tutoring did have a small positive impact on reading test scores, it did not lead to any improvement in math scores. Additionally, tutoring failed to boost course grades in either subject. Kraft acknowledged that the results were not as significant as many had hoped for, especially considering the large investments made in these programs.

Challenges Faced by Tutoring Programs

One of the major challenges faced by tutoring programs in Nashville was the sheer scale of the initiative. Unlike previous small-scale tutoring studies that involved fewer than 50 students, Nashville’s program reached almost 7,000 students, making it significantly larger in scope. This presented logistical challenges, such as coordinating tutoring sessions, managing technology issues, and ensuring that students received individualized attention.

Initially, Nashville’s tutoring program relied on remote tutors, including college student volunteers, to provide academic support. However, this approach proved to be inefficient and ineffective, leading the city to switch to in-person tutoring by teachers at the schools. While this change eliminated some of the technological challenges, it also highlighted the limitations of having fewer teachers available to tutor multiple students simultaneously.

Despite the challenges faced by the tutoring program, there were some positive developments over time. The average number of tutoring sessions attended by students increased, indicating a growing engagement with the program. However, the overall academic gains from tutoring remained modest, prompting a closer examination of the program’s design and implementation.

Implications for Future Tutoring Programs

The disappointing results of the Nashville tutoring program raise important questions about the effectiveness of mass tutoring initiatives, especially in the post-pandemic era. Kraft emphasized the need for researchers and educators to recalibrate their expectations and focus on identifying which tutoring programs and design features work best for different groups of students.

One possible explanation for the lackluster academic gains from tutoring is the presence of other interventions, such as personalized learning time and educational software, that students were also receiving in Nashville schools. These alternative approaches may have competed with tutoring for students’ attention and resources, diluting the impact of the tutoring program.

Moving forward, it will be crucial for schools to strike a balance between different forms of academic support and tailor interventions to meet the specific needs of students. While tutoring may not be a one-size-fits-all solution, it can still play a valuable role in helping students who are struggling academically.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study conducted by Matthew Kraft and his team sheds light on the complexities and challenges of implementing mass tutoring programs in schools. While the results may not have been as promising as initially hoped, they provide valuable insights for future efforts to provide academic support to students.

As educators and policymakers continue to navigate the post-pandemic education landscape, it is essential to remain open to iterative experimentation and continuous improvement. While tutoring may not be a panacea for academic recovery, it can still be a valuable tool when implemented thoughtfully and in conjunction with other interventions.

Ultimately, the goal of tutoring programs should be to provide students with the personalized attention and support they need to succeed academically. By learning from the experiences of programs like the one in Nashville, schools can better tailor their approaches to meet the diverse needs of students and help them thrive in the classroom.